Sunday 6 November 2022

ALL ASSIGNMENTS LINK

Paper-105 Assignment: Victorian Era

Name: Drashti Joshi

Batch: M.A. Sem.1 (2022-2024)

Enrollment N/o.: 4069206420220016

Roll N/o.: 06

Subject code & Paper N/o.: 22395- Paper 105: History of English Literature- From- 1350 to 1900

E-mail Address: drashtijoshi582@gmail.com

Submitted to: Smt. S.B. Gardi Department of English- M.K.B.U.

Date of submission: 7th November, 2022

Work cited:

Adams, James Eli. A History of Victorian Literature. Oxford: Blackwell, 2012.

“An Introduction to Victorian England.” English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/story-of-england/victorian/. Accessed 6 November 2022.

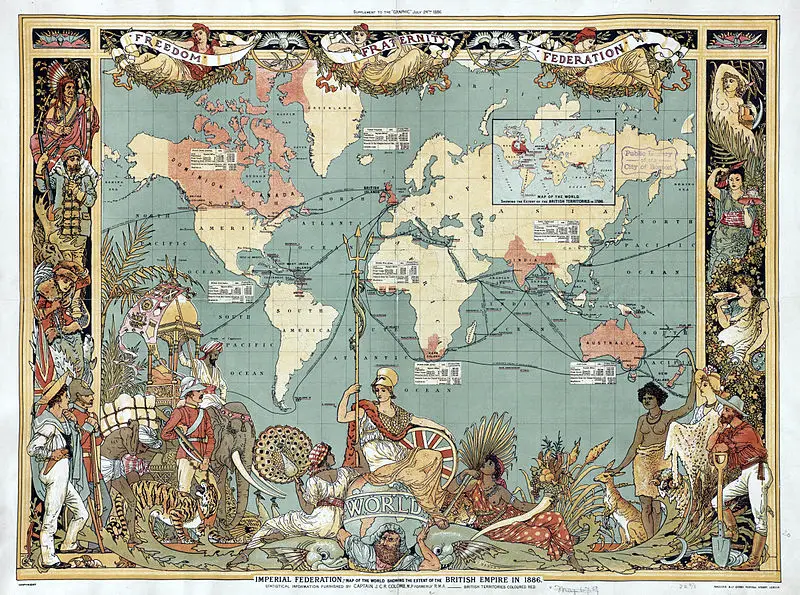

Ireland, Alleyne. “The Victorian Era of British Expansion.” The North American Review, vol. 172, no. 533, 1901, pp. 560–72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25105153. Accessed 6 Nov. 2022.

The Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Victorian Age. Ed. Carol T. Christ and Catherine Robson. New York: Norton, 2006.

Shepherd, Anne. “The Victorian Era.” History in Focus: Overview of The Victorian Era (article), April 2001, https://archives.history.ac.uk/history-in-focus/Victorians/article.html#one. Accessed 6 November 2022.

{Images-14}

{Video-02}

{Pages-18}

Paper-104 Assignment: symbols in Hard times.

Name: Drashti Joshi

Batch: M.A. Sem.1 (2022-2024)

Enrollment N/o.: 4069206420220016

Roll N/o.: 06

Subject code & Paper N/o.: 22395-

Paper 104: Literature of the Victorian era.

E-mail Address: drashtijoshi582@gmail.com

Submitted to: Smt. S.B. Gardi Department of English- M.K.B.U.

Date of submission: 7th November, 2022

Symbols in ' Hard Times'

Dickens uses symbols in his novel in order to give an exact shape to his moral purpose. Most of the characters in the novel are an embodiment of a certain idea or principle. There are two groups of symbolic characters: one symbolizing the objectionable qualities of Victorian life, and other symbolizing certain positive qualities and these two opposite poles are confronted with the novel.

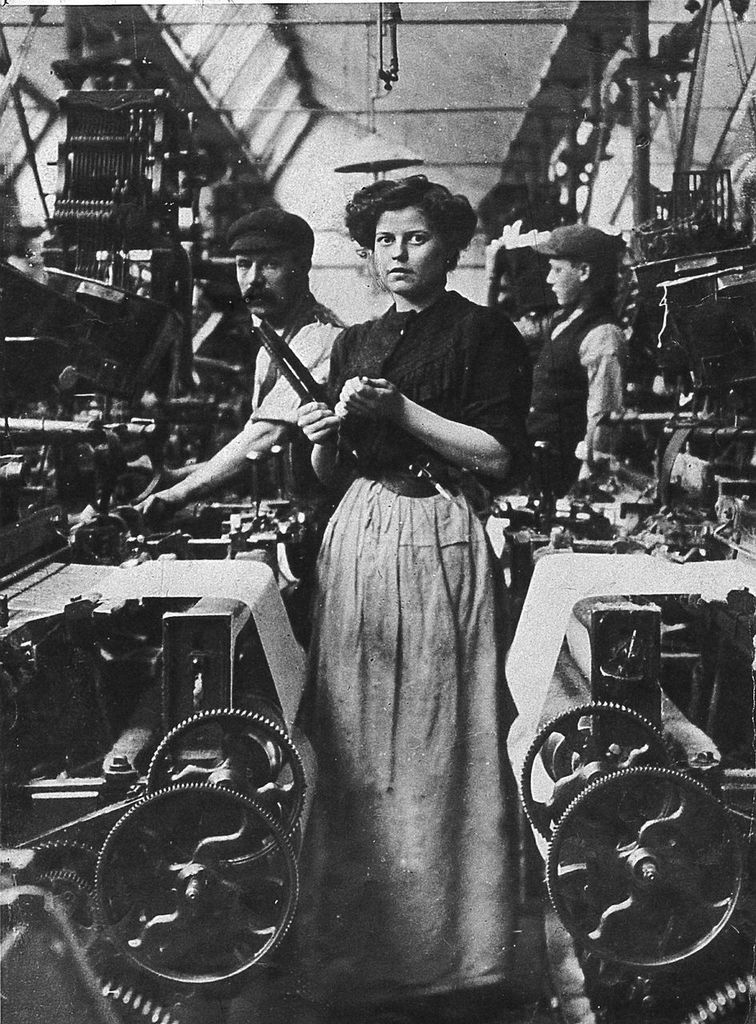

Dickens not only uses characters as symbols, but the setting of Coke town as a brick jungle as it is the symbol of ugly industrialization. The industries and factories scattering in the towns make the city dirty with black smoke symbolise unnatural death of the workers by the modern monster like machines.

Among the characters who symbolise vice, evils, abuses and pitfalls of the ugly society is Mr. Gradgrind who holds the first and foremost position in his society. He successfully symbolises the negative qualities of the utilitarian education system. He entirely focuses on the facts, calculation and numbers and denies the attachments with fancy, love, emotions and imaginations. He is the rigid and blind follower of the absurd utilitarian educational theory. What he gives importance to is just the factual knowledge not the practical learning because of which he has to lose the charm and beauty of his children’s lives.

Another major character Bounderby, the banker and manufacturer, is the symbol of utilitarian economic theory and the theory of Laissez Faire (the theory which believes that economy works best if private industry is not regulated and markets are free). This ugly man represents the greed for money and inhumanity in his practical life. When it comes to the fulfilment of the basic requirements of his workers, he turns his deaf ear and moreover he dismisses Stephen Blackpool.

The daughter of Gradgrind, Louisa becomes the symbol of the suffering and victim of wrong education, upbringing, imposition of fact, avoidance of imagination from one’s life. She receives our sympathy when she can’t identify her feeling of love and pain. Tom, brother of Louisa, too symbolises the same dangerous product of his father’s absurd theory of education and upbringing. Bitzer symbolised another evil of the then existing society and culture. He is the best product of Gradgrind’s principle of education for whom everything if the matter of bargain and is controlled by self-interest. Mrs. Sparsit becomes the symbol of snobbery and hypocrisy of the upper class of the Victorian era.

The other group of people who represent positive features of that society are Stephen Blackpool, Rachel, Sissy Jupe and the Circus. Stephen and Rachel are the symbol for noble minded and generous persons. Sissy Symbolises vitality as well as goodness: she has a golden heart and is full of spirit of service. She represents the opinion of the antithesis of calculating self-interest. The circus and its people are the symbol of humanity and art where different colours of life are counted and emotion, sentiments have right place and value

Mrs. Sparsit, who has not quite gotten over having to leave Mr. Bounderby's house to make way for Louisa, maliciously watches the affair between Louisa and Mr. Harthouse progress with glee. As the two slowly draw closer together, she imagines that Louisa is slowly descending a great winding staircase. Down, down, down she goes…and when Louisa finally elopes or disgraces herself publicly in some other way with Mr. Harthouse, Mrs. Sparsit imagines her stepping off the bottom of the staircase and falling into a dark abyss. Louisa, of course, never quite falls off this staircase as she refuses to elope with Mr. Harthouse.

Pegasus:

The Pegasus's Arms is the name of the tavern at which the circus company is staying when Sissy returns with Mr. Gradgrind and Mr. Bounderby to find her father gone at the very beginning of the novel. Pegasus, a mythical winged horse, represents the imaginary and fantastical world in which imagination is allowed to soar: a world the Gradgrinds are forbidden to experience. It is the perfect residence, on the other hand, for Sissy's father's circus company, who make the world of magic and fairy stories come to life. This is what gives Sissy such a good heart: free exercise of her imagination and her heart.

Smoke Serpents:

At a literal level, the streams of smoke that fill the skies above Coke town are the effects of industrialization. However, these smoke serpents also represent the moral blindness of factory owners like Bounderby. Because he is so concerned with making as much profit as he possibly can, Bounderby interprets the serpents of smoke as a positive sign that the factories are producing goods and profit. Thus, he not only fails to see the smoke as a form of unhealthy pollution, but he also fails to recognize his own abuse of the Hands in his factories. The smoke becomes a moral smoke screen that prevents him from noticing his workers’ miserable poverty. Through its associations with evil, the word “serpents” evokes the moral obscurity that the smoke creates.

Fire:

When Louisa is first introduced, in Chapter 3 of Book the First, the narrator explains that inside her is a “fire with nothing to burn, a starved imagination keeping life in itself somehow.” This description suggests that although Louisa seems coldly rational, she has not succumbed entirely to her father’s prohibition against wondering and imagining. Her inner fire symbolises the warmth created by her secret fancies in her otherwise lonely, mechanised existence. Consequently, it is significant that Louisa often gazes into the fireplace when she is alone, as if she sees things in the flames that others—like her rigid father and brother—cannot see. However, there is another kind of inner fire in Hard Times—the fires that keep the factories running, providing heat and power for the machines. Fire is thus both a destructive and a life-giving force. Even Louisa’s inner fire, her imaginative tendencies, eventually becomes destructive: her repressed emotions eventually begin to burn “within her like an unwholesome fire.” Through this symbol, Dickens evokes the importance of imagination as a force that can counteract the mechanization of human nature.

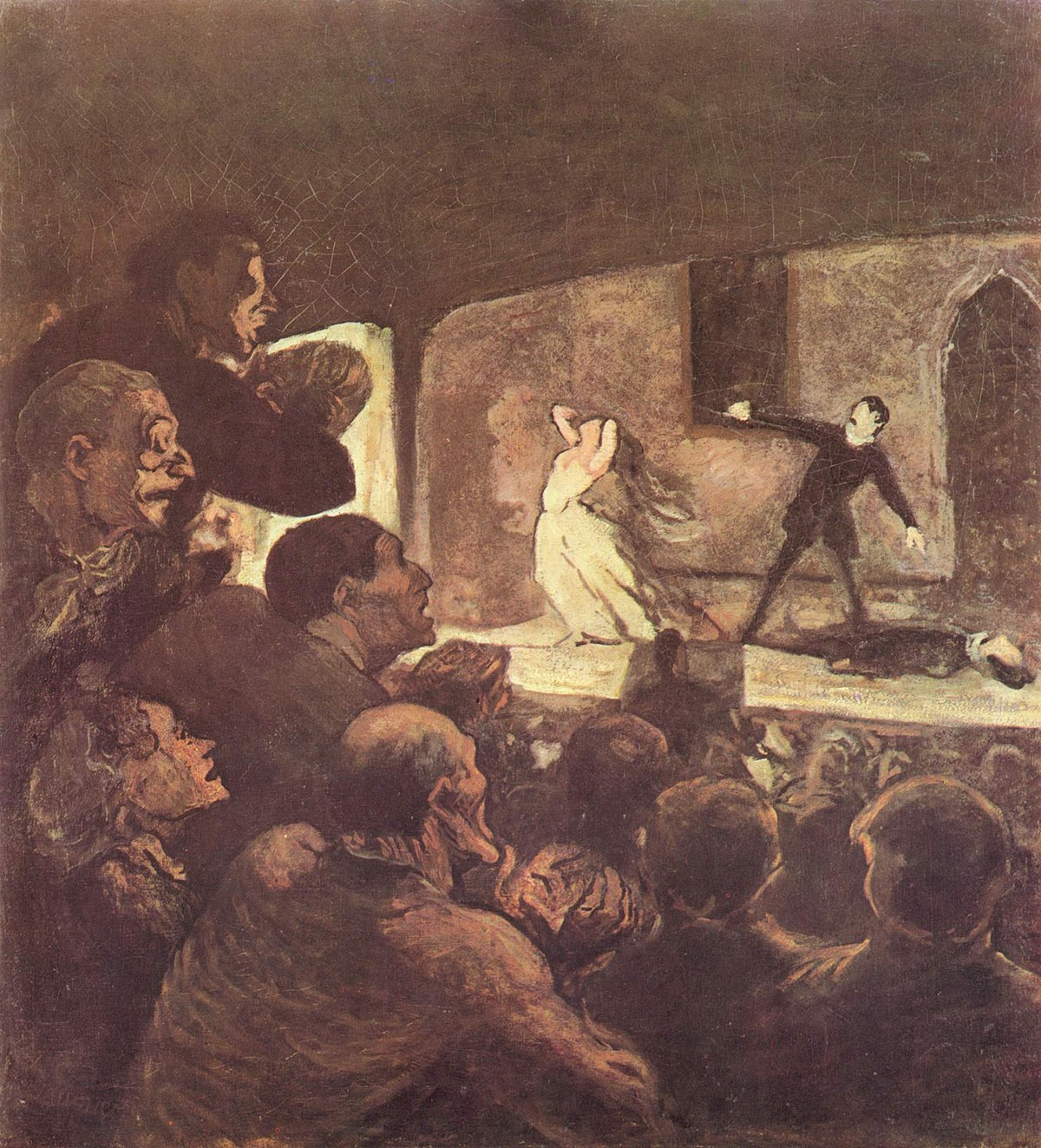

Circus:

With clowns, acrobats, and elaborate horse-riding shows based on legendary themes, the circus symbolizes the triumph of imagination and whimsy, or what Mr. Gradgrind would call "fancy." The circus features such performance pieces as the enticingly named "equestrian Tyrolean flower-act," which presumably combines flowers and horses in a creative way. Another performance features Master Kidderminster as Cupid, complete with "curls, wreaths, and wings." These performances provide factory workers an escape from the monotony and squalor of everyday life.

Even though wealthy men such as Mr. Gradgrind and Mr. Bounderby dismiss circus performers as disreputable slackers, circus performances require great skill and extensive training, showing the variety of expertise and ability that can lead to a productive and satisfying life, one most definitely not based on fact. The circus represents not merely the escape entertainment provides but also a broader understanding of what success and prosperity can mean. The dismissal of the circus, in turn, represents a restrictive worldview that neglects the validity of fanciful human joy.

Bank:

In complete contrast to the haphazard whimsy of the circus, the bank is a regimented and organized space, cleaner than the factories but dismal and restrictive in its own way. It is part of "the wholesome monotony of the town," a red brick building nearly indistinguishable from the other red brick buildings that surround it. The desks in the office space are set up in rows that echo the rows of machines in a factory, and Tom Gradgrind finds his place in the bank as oppressive as Stephen Blackpool finds the factory—perhaps more so. It is a privileged but dull existence. As a symbol of wealth, the bank shows how wealth oppresses those who don't have it. The images of heavy doors and locks emphasize how the money is kept separate from all human eyes and hands.

The building itself, as well as the institution, is a symbol. A nondescript but imposing brick structure, the bank is inaccessible to those who do not have money, and thus serves as a physical reminder of what people living in poverty can never obtain.

Animal:

It is a striking feature of Hard Times that the novel begins with the question of how to define a horse, just as E. M. Forster's novel The Longest Journey begins with the philosophical words : "The cow is there." Indeed, the symbols of animals, as well as those of flowers, frequently appear, and are sustained throughout the novel. I think that Dickens's sustenance of these symbols in the novel is far more significant than is generally supposed because he offers us two incompatible types of characters by presenting the fundamentally different interpretations of these symbols. Dickens's way of introducing animal and flower symbols is skillful. The reader first encounters these symbols in the scene of the Gradgrind school, where Mr. Thomas Gradgrind, an "eminently practical" gentleman, makes "Girl number twenty" (Sissy Jupe) define a horse. Though she and her father belong to Mr. Sleary's travelling (horse-riding) circus and though she has been brought up among a lot of horses, she cannot answer him at all. Bitzcr defines a horse very well, using the dictionary's definition. Mr. Gradgrind seems content with this model pupil's definition. Then, a government officer steps forth and asks the pupils whether they would "paper a room with representations of horses" To this question one half of the children answer in the affirmative but he forces them to answer in the negative. Mr. Gradgrind is also in the same opinion as his companion. It seems unreasonable to have the representation of horses on the wall. Now, this government gentleman asks the children whether they would use "a carpet having a representation of flowers upon it ." Sissy is one of "a few feeble stragglers (who) said Yes," because she is "very fond of flowers." Then, she is asked why she would "put tables and chairs upon them, and have people walking over them with heavy boots." Sissy's answer is : "It wouldn't hurt them, sir. They wouldn't crush and wither if you please, sir. They would be the pictures of what was very pretty and pleasant, and I would fancy—" She is interrupted by the gentleman's cry : "Ay, ay, ay! But you mustn't fancy"

Thank you so much for reading this Assignment.

{Words-1787}

{Images-11}

{Videos-01}

{Pages-08}

Saturday 5 November 2022

Paper-103 Assignment: Marriages in Pride and Prejudice

Name: Drashti Joshi

Batch: M.A. Sem.1 (2022-2024)

Enrollment N/o.: 4069206420220016

Roll N/o.: 06

Subject code & Paper N/o.: 22394- Paper 103: Literature of the romantic period.

E-mail Address: drashtijoshi582@gmail.com

Submitted to: Smt. S.B. Gardi Department of English- M.K.B.U.

Date of submission: 7th November, 2022

Marriages in Pride and Prejudice: by Jane Austen

In general, the situation of women in the Victorian age and more specifically the marriage in the Victorian age and how the women were approaching marriage. There were many reasons behind conducting marriage by women in the Victorian age, for example, many women were conducting marriage because their social status was not good or they had a poor family therefore they were relying on marriage to secure their future, while there were many others trying to do marriage just to get economically some interests or money. In this study we have chosen the novel of Pride and Prejudice to explain more clearly the conditions women were experiencing at the time, our first novel is Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. In Pride and prejudice Jane shows multiple-marriages and the reasons stand behind each marriage. Jane clearly comments about each of these marriages and reveals her preferred marriage and she encourages women to conduct companion marriages because he sees them as the most successful marriages.

Keywords: The Victorian era ,Marriage in Pride and Prejudice.

Introduction:

Literature of the nineteenth century put a great emphasis on the concept of marriage as a social institution. In this century domestic fiction displays a great shift in marriage from an aristocratic institution to a socially accepted institution that identifies the values of the individual woman while restricting her to the domestic sphere. If we pay a close look to the novels Pride and prejudice by Jane Austen , the change in marriage can be seen from an institution set up by the ageing rules of an aristocratic community to an institution that introduces the value of the individual woman. Domestic fictions show how the attempts toward individuality encouraged the middle class women with a sense of an intendancy and a capacity to create autonomous decisions. The women’s issues were forming the most critical points of the novels in the Victorian age; they were specifying the points and showing them to the public. In the Victorian age the society had many problems and the condition was one way far from the solutions. The social class difference in the Victorian era was the most devastating and toughest problem of the Victorian age. The difference in classes reflected in every aspect of life and this difference sharpened the life of the middle and the lower classes.

Women as a major part of society did not stand out of this discrimination, but instead they almost likely received the largest portion of this difference. The social class difference negatively left a strong impact on the way of women’s marriage in the Victorian era, for example, for a woman to be able to conduct a marriage her social status was very important and it was something looked at seriously by the man who wanted to marry her. The family’s condition was a reason that a poor woman could not marry a man from a high position or class and even if she had married a man of that position the society would have stood against her and not allowed that to happen because it was against one of the concepts of the Victorian society‘s rules. The women’s situation in the Victorian era was too intense. The Victorian society was more a patriarchal society; therefore, there was always an obstacle in front of women wherever they wanted to go. Women’s contribution was at a low rate, and women were not allowed to work outside of home. Victorian society kept a conservative concept in which it did not give permission to women to work in public; it was looked at as a kind of shame on the family if a woman worked out. The Victorian society appointed women only to domestic tasks. They believed women had to stay home, do house holding and raise children. These boundaries made women economically weak and dependent on her husbands .Women did not have any sources to afford money except their husbands. The women’s education was poor. Victorian society had a strict view about women’s education and they saw it unnecessary for women to study, they were not supplying women with money to complete their study.

Women’ were looked at as men’s property. Victorian society considered women as property men could inherit it, whatever she had of money or any property would be her husband’s property including herself. There was not any law giving women’s right to inherit or possess anything left by their family for them. Women’s voices were not heard anywhere. There was also an obstacle in front of women to participate in the elections, and it was shown that politics is a men's sphere and not necessary for women to involve herself in politics, therefore, women were not allowed to choose someone to represent and be there for them in parliament. In particular, this study examines marriage in the Victorian age by choosing the novel of Pride and Prejudice which shows different aspects of marriage in the Victorian age with regard to the time they lived in. The novels are Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. This study shows the different points mentioned in this novel, and the purpose written for. Through reading this novel this work tries to provide the real life women experienced in the Victorian age, and to mark the factors standing behind hindering women from any contribution either they are social factor or political factor or both together. The aim of his study is to shed light on the conditions women met at that time and to give a proper picture of that century and we specify ourselves in marriage and the issues women were facing when they wanted to conduct a marriage. Jane Austen is also one of the authors who came to life in 1775 and published Pride and Prejudice in 1813. Jane was one of the novelists in England whose writings serviced English literature and the women of the Victorian age. In Pride and prejudice she devotes the entire novel to the marriage issue in the Victorian era. She shows different marriages and reasons behind each marriage. In this novel she encourages women for marriage and she suggests women to conduct marriage based on love and not money or interests. She prefers companionate marriage because in this marriage married couples form their marriage on the basis of love and they both have economic responsibility towards family and they are there for each other at times of difficulties. She supports the Companionate marriage because it includes the equality of souls and the rise of individuality. She displays the shortcomings of the marriages which are not based on love but also based on fulfilling desires and pleasures. The attempts these authors made led to the growth of many movements and organisations concerned about the rights of women. Many constitutions by the middle and the end of the Victorian age appeared and all these influenced the situation of women for better.

Marriage in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice:

The Marriage between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet Jane Austen, the writer of Pride and Prejudice in this work concentrates on one point; she believes that marriage should be a formative institution in which two individuals can play as two equal souls. She argues if a girl and boy get married as two equal souls or two equal people, with no regard for class and money, just love and understanding each other, then they will probably have more chance to use their marriage to complete and learn from each other as individuals. In this novel Jane Austen is more concerned about discussing a successful marriage or companionship between wife and husband. She sees this easy if they have a foundation where they can build up their marriage on. Jane Austen might be shown as a visionary for her times. She differently represents marriage and draws a line between marriage in past times and her times. She tries to tell people to avoid marrying a financial equal but the (soul’s equal)-, the one who will encourage their individual improvement. In particular, Pride and Prejudice characterises females whose marriages reflect their different desires for marriage. The option of choosing is the key, because the choice determines the personal view of and motivation for marriage. It could be a sexual pleasure, executed position or whetstone; a person who sharpens, Pride and Prejudice shows these motivations for marriage. Even though all these reasons are not exhibited in the best light by Austen, having this in mind, she is also aware of her time and she is hopeful that the institutional model of marriage may develop in every period. By noticing these kinds of marriage present in the novel, marriage reaches its purpose when it is shown as a formative foundation-one that ties two people together at the growing stage in forming their own identities and matures one another as they grow together. The marriage between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet is not working because they are an ill-suited couple. The marriage, however not sickened by any kind of brutality or humiliation, does not respond to the growing idea of the “companionate marriage” in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. The companionate marriage needs a “complete form of integral companionship, formed on reciprocal limit, tolerance and mutual respect.The marriage between Bennets is in a long distance with respect and conjugal companionship .Their marriage, in fact, characterises stupidity and disregard. At the beginning of the first chapter, it is clear that Mr. and Mrs. Bennet are uncomfortable with each other. Austen pictures Mrs. Bennet, expressing, “her job in life was to get her daughters married”. John Lauber observes that her personality is small-minded and not strong and she is a person of absolute dependence on her society.Similarly, Austen defines Mr. Bennet’s marriage condition and she displays his constant exhaust especially from his wife delights and happiness. She pretends she is not anymore concerned about what is going on between them and their relationship but more concerned about her happiness and her daughters’ marriages .Despite their unhappiness; they seem comfortable in their inactive state of marriage. They are satisfied whether on purpose or not about their marriage state. The two couples don’t try to make any change in their marriage state and it seems they don’t see the need for progress in their marriage. Mr. Bennet has been criticised because of lack of commitment to his marriage on the side of a father and a husband. Jane provides enough reasons explaining how Mrs. Bennet also holds the same responsibility in this manner as Mrs. Bennet.

The marriage failure of Mr. and Mrs. Bennet goes back to their different comprehension for marriage, originating in two self-seeking motivations for their relationship. The reasons they had for marriage did not stand alongside the ones of companionate models. If they had understood each one's motivation for marriage, they might have been able to cool off the struggle between them .Although, it is clear to confess that before they decide to get married, they do not know each other well and do not have information about each other. Christopher Brook, in his book Illusion and Reality, claims that the two did not know a lot even about each other and did not hold a lot of information on each other before they engaged. Therefore, after the marriage Mr. Bennet realized what a stupid, weary woman he has married with.

Unfortunately, Mr.Bennet's realisation about her immature identity deepens just when his love he has for her breaks down to nothing. The misled motivations drove Mr.Bennet to marriage and left him with feelings of affection or love, but once that love stopped, satisfaction replaced its place. Mrs. Bennet was at the beginning of her youth, she was beautiful and attractive at the same time she possessed a spirited personality. Mr.Bennet probably was distracted by infatuation and did not seem he closely looked at her and read her mind. It appears that the time Mr. and Mrs. Bennet decided to get married; they nearly owned an immature personality in understanding their own selves. In fact, as the relationship between them intensifies they don’t spend any time together and they stay away from each other. Mr. Bennet decides to give up on her and takes a book with himself. He was mostly in his library. It is his excuse. A library is a place where he conceals himself from his wife and discovers his desired enjoyment. It has been twenty three years they are still in this way, he in his library and her in her living room. They both remain apart from each other.

The Marriage between Mr. Collins and Charlotte:

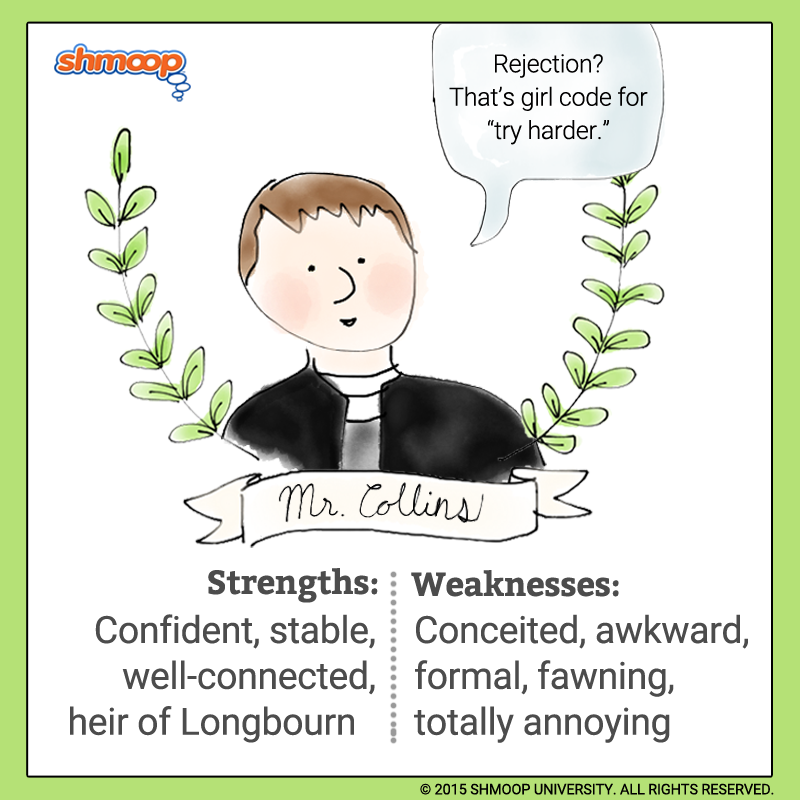

Mr. Collins and Charlotte is a marriage of parallel living. Marriage seems more like the marriage of roommates rather than soul mates. The lifestyle they live before their entrance into marriage remains pretty unaffected even after their marriage. Even though they have different reasons for marriage, they never allow a friend or companion to enter their private life and form their marriage for them. Moreover, they simply show partnership as doable. Rather, they simply view a spouse as a practical and profitable meeting of their personal necessities. When Mr. Collins and Charlotte Lucas enter into marriage, they have already set up their ways, instead of fueling disagreement or toughness like the Bennets, they settle into a distant and satisfied relationship which has originated from their overly rational thinking of marriage. Charlotte deepens her conception of marriage in reason, and she enters into marriage because of her needs to stabilise her future. At the very beginning of the novel she is twenty-seven and yet not married. For her being single would leave some stress on her; she remains an old maid . It sounds that the interaction of her anxiety and her practicality lead Charlotte Lucas to marry Mr. Collins. Austen enlarges the pragmatic view that Charlotte holds about marriage in her conversations with her sister Elizabeth she discusses her reason for marriage with confidence. This conversation starts when Mr. Bingley proposes to Jane Bennet. Charlotte and Elizabeth notice this proposal; Charlotte says Jane has to hold on to Mr. Bingley before even she knows what feelings he has for her, and her feelings for him. Elizabeth denies by saying “Your plan is a good one . . . where nothing is in question but the desire of being well married; and if I were determined to get a rich husband, or any husband, I dare say I should adopt it”. Elizabeth bravely homes in on her friend’s main purpose regarding marriage-to get a husband, for Charlotte, any husband. She tells her perspective of marriage clearly: happiness in marriage is a matter of chance. Elizabeth sarcastically responds that our words are great, Charlotte; but it is not that way. You know it never works that way. Charlotte even after this conversation does not change her view about marriage and instead she keeps her faith in chance when she agrees Mr. Collins proposal.

The Marriage between Wickham and Lydia:

The Marriage between Wickham and Lydia characterizes an incomplete growth or continuity in their undeveloped paths. Lydia is at the age of 16, and Wickham is relatively immature in his behavior though not in an age to get married. Their marriage suggests as a great indication that the writer does not encourage this kind of marriage and does not want people to get married while they are not wholly formed. In contrast, she wants to convey her message that the individual should be grown to some extent before entering marriage, even after marriage there is still opportunity to grow with his or her spouse. In the case of Lydia and Wickham, both are still young in their development. Motives stand behind their marriage “self-serving and pleasure seeking, which does not result in a successful marriage environment. In reality, it is because of their undeveloped and self-seeking wants that they end up marrying at all. To look at the other side of the spectrum, Lydia is still evidently immature in her personality when she decides to get married. She escapes with her lover Wick when she is at the age of sixteen. She seems too naïve regarding her motives and her mind. She tries to entertain herself either by dancing or, surpassing her sister Kitty, or trying to attract men in the regiment .Lydia has a weak understanding about who she is. She flits from boy to boy and at the time she is left her way, falls into panic. Elizabeth complains about her sister's weak aspirations. Lydia has an unformed mind which is exactly identical to her mother’s mind, and it is the why Mrs. Bennet prefers Lydia more among the rest of her daughters. Lydia thinks that Wickham planned to marry her and after escaping she pretends to be unaware of Wickham’s plan. Lydia’s honest unawareness and juvenile behaviour reach a high point in her short letter to her sister Elizabeth.

Relatively, Austen shows several marriages and their faults, at the same time she also lists marriages that hold certain powers that she looks to encourage them rather than accuse; the two marriages one between Jane and Mr. Bingley and the next one Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy as well. More often Austen has a satiric authorial tone in her attitude towards her characters. Even she approaches the marriage between Jane and Mr. Bingley, with a twinge of humour. She honestly discloses the clear faults and strengths of their marriage. At the beginning of their marriage both are more moldable by their friends. While their vulnerability badly impacts their relationship at first, it helps them learn from one another and institute a healthy growing relationship in the end.

References:

Austen, J., (2007). Pride and Prejudice, New York: Vintage Books.

Austen, J., (1993).Jane Austen, London: Aurum. Brooke, C.N.L.,(1999).

Jane Austen: illusion and reality, Woodbridge, Suffolk: D.S. Brewer.

Lauber, J.,(1993). Jane Austen, New York: TwayneHammerton.A.J.,(1990).Victorian Marriage and the Law of Matrimonial Cruelty. Victorian Studies.

{Words- 3000}

{Images-07}

{video-02}

{Pages-11}